I’ve been to this museum a few times before, sometimes for talks and sometimes to just look around it. I always manage to learn something new.

This time I was looking around with a friend’s daughter who is currently studying in Manchester. As she was originally from Manchester, but moved away as a child, this was a good place to re-introduce her to her roots.

The museum curates ordinary history. The history of the ordinary man and woman rather than Kings and Queens and wealthy movers and shakers. And Manchester, birthplace of the industrial revolution and with a reputation as a hotbed of radical thinking throughout the ages, certainly has lot of extraordinary ordinary history.

Here are a few highlights.

The museum is spread over three floors. The first floor covers the story up to 1945 with four main sections: Revolution; Reformers; Workers and Voters. The story continues up until the present day on the top floor, which is also where the museum’s magnificent collection of banners is housed. Back down on the ground floor you can find the shop, cafe and a gallery of changing exhibitions.

The sculpture pictured above (also the feature photo for this post) curves around the walkway as you enter the first floor gallery. It was commissioned by the museum for this space and represents everyone who has fought for the vote, equality, justice and the freedoms we have today.

This sculpture depicts how workers’ relationship with time changed during the industrial revolution. Factories needed cheap workers and the sculpture shows a couple of struggling mill workers, a child labourer and a shackled slave. The slave is a reminder that much of the growing wealth of Manchester (and Britain as a whole) was dependent on the imported cotton grown by slaves. All four figures are shown holding onto and, at the same time, resisting the turning hand of the clock.

The Chartist movement, named after their charter of six demands, was the world’s first working class movement. Amongst their demands was the call for the vote for all men over 21. Their petition was rejected. At this time, economic depression meant many jobs were lost (one in four cotton workers in the Lancashire town of Preston lost their jobs) and the Poor Law Amendment Act saw these men harshly treated as poverty was declared a crime. Meanwhile, other laws were disappointing for those who kept their jobs (the failure of new legislation to limit the working day in factories to 10 hours, for example).

Many of the working class saw the Chartist Movement as their only hope for change and the whole of the North West reacted with a strike. During the ensuing disturbances at least eight men from Preston were shot by the army. Four of them, aged between 17 and 27 were killed, their deaths being ruled ‘justified homicide’ at the inquests.

A full size sculpture dedicated to the men stands in Preston and the above photos show the maquette of it in the museum. In the actual sculpture the men look as though they are cowering from the soldiers leading some people to claim the sculpture is inaccurate as the men, rather than cowering, stood strongly in the face of adversity and demanded their rights because they had had enough of being suppliant. This post explains this argument. The finished sculpture looks quite different to the maquette and I have to say I prefer the maquette. I wonder what happened to make Gordon Young give the men an appearance of fear and pleading rather than defiance in the finished statue?

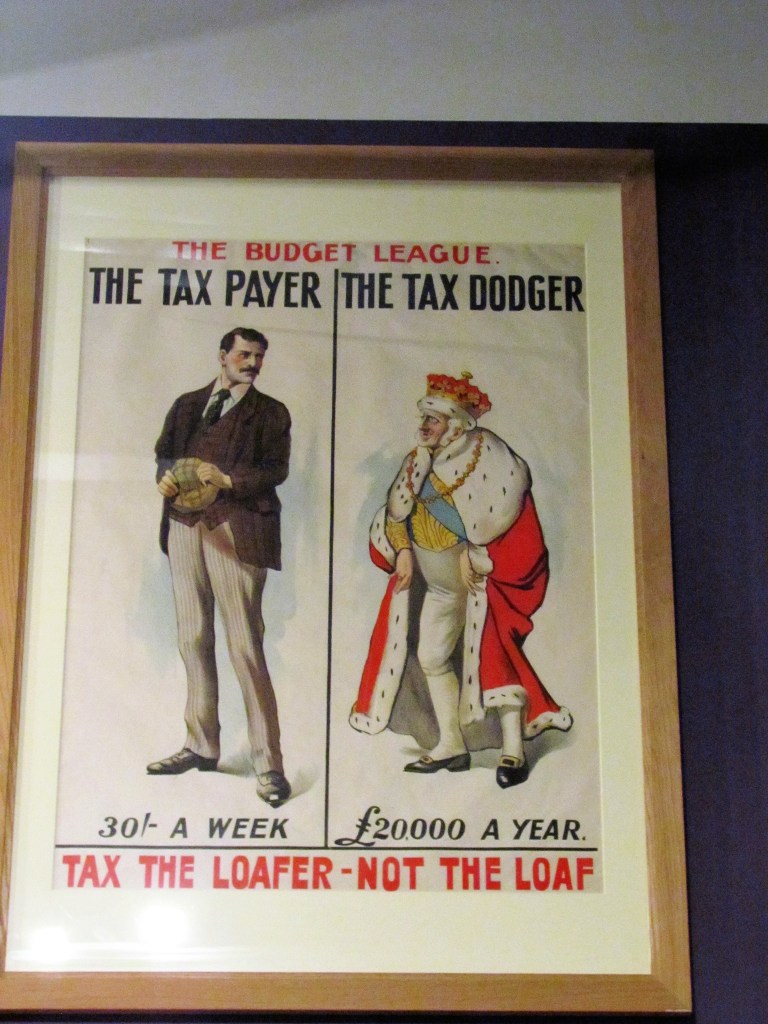

Throughout the museum are items with sentiments, that although they were from years ago, could easily be from today. It really brings home how we never learn and keep letting history repeat itself. This has never seemed more relevant to realise than it is in the current political climate.

Worried about ‘swarms’ of immigrants coming to take your job? And not nice, clean and well-behaved, culturally acceptable immigrants either, but heaving hordes of unwashed, uncivilised barbarians? Well this isn’t a new worry. Way back in 1796 people were worried about the same thing. Only difference then was that the immigrant masses were Scots.

Richard Newton’s cartoon stereotypes the hundreds of Scotsmen who were coming to take English jobs. They are portrayed as unkempt and immoral with their bare bottoms on display beneath their kilts. The brooms they are carrying were supposedly used as scratching posts to relieve their itching as they never washed.

This poster is another example of how some things never change!

A few things have changed though. Could you imagine a Conservative poster like the one below today? I know the Conservatives are still not above scapegoating a particular group in society (I’m thinking of you Theresa May with your ‘Go Home’ buses and texts wrongly sent to people living here legally), but I still don’t think they’d come up with a poster like this anymore.

I don’t know what year this poster was from, but maybe the Tories were getting worried about gay people because they were supporting the miners.

This poster reminded me I’ve still not watched Pride even though I’ve had it sitting on my shelf for ages. In case you don’t know Pride is the film made about the unlikely alliance between members of the gay community and striking miners in 1984.

This is a poster which until last year I would have said was showing something from bygone years which had no chance of happening now. I’m not so sure anymore.

In the case of this poster I’d be quite happy for history to repeat itself. I’d love the opportunity to be a £10 pom. The Assisted Passage Migration Scheme was the brainchild of Australia’s Ministry for Migration in 1945. The Government realised that industry was booming and they needed to increase the population in order to ensure an adequate supply of workers, and so offered Brits a £10 passage to Australia. Over a million white Brits took up the offer and emigrated, with 400,000 applying in the first year. I specified ‘white’ Brits because the country had a ‘White Australia Policy’ at the time which meant the offer was only open to white Britons. How bad does that sound today?

As well as posters, the museum acts as a retirement home for a large number of trade union banners – the really huge ones that are used on parades and marches. The banners are changed periodically and so you may see different ones displayed if you visit again. A textile conservation room is glassed off from the gallery and so during the week you can sometimes watch as the banners are painstakingly restored and preserved.

As well as posters and banners there are plenty of artifacts in the museum. These two swords belonged to a man from Droylsden who rode with the Manchester Yeomanry at Peterloo in 1819.

The Peterloo Massacre occurred when cavalry charged into a crowd of 60-80,000 who had gathered in St Peter’s Field (now a busy square in Manchester city centre) to demand parliamentary reform. Although hundreds were injured, amazingly ‘only’ 11 were killed.

The swords were of interest to me as Droylsden is my home town. At the time of Peterloo it will have been just a small village. I wonder whereabouts he lived and if the house is still there?

This coffin has the sign on the front stating ‘Here lies knowledge. Open at your peril’. Not wanting to turn down a bit of knowledge we risked our peril, gingerly opened the lid and found the inside was stuffed with …

… newspapers!

Newspapers were taxed until 1836 and this was seen as a tax on knowledge. The newspapers were stamped to show the tax had been paid. Sellers who were avoiding the tax or had illegal papers for sale (those critical of the government) sometimes moved them around in coffins as government officials were unlikely to search a coffin.

The activity on the table pictured above involved turning a flat piece of card into a matchbox. There were clear instructions on where to make the folds and slits in the right places. We flipped the egg timer then raced each other and the time to complete a matchbox. If we could make them in less than a minute we’d have made a decent living for ourselves back in the day. Two minutes and life would have been a lot more dismal. Three minutes or more and we’d have been sacked and in the workhouse.

Charlotte just about kept her job, but I was definitely destined for the workhouse. I’m putting it down to her being so much younger than me and therefore having more nimble fingers.

I have no excuse though for why, when we compared our finished products, mine was inside out.

As it was nearly closing time (we’d managed to spend nearly three hours looking at everything), we just had time to have a quick look at the special exhibition on the ground floor. This was a collection of photographs taken by ordinary people in Syria using everything from DSLRs to phones. The photographs document what everyday life in Syria looks like now and provide testimony to the destruction their country is undergoing.

I would have liked more time to spend taking in these photos and the very real lives they represent but the museum was closing. As it’s only a temporary exhibition it will no doubt have finished next time I’m here.

If they ever let me out of the workhouse that is.

Did any of the exhibits surprise you? Do you believe history is destined to repeat itself or are you confident we can learn from our mistakes? Share your thoughts in the comments below.